This blog has always been in English, because I want my foreign friends and others around the world to be able to read my posts. Likewise, academic life in Sweden is increasingly becoming oriented towards English as the standard language, especially when it comes to publications. But there is nothing that I love as much (well, intellectually speaking) as writing in Swedish! It’s of course nice – and nowadays totally necessary – to be able to publish books and articles in English as an academic lingua franca. But I’m sometimes surprised how many of us unthinkingly turn to this foreign language to express ourselves as often as we can. I’m firmly convinced that Swedish scholars need to continue expressing themselves in Swedish as well.

Perhaps that’s an impossible equation? I mean, to write in both English and Swedish. Our time is limited and if we prioritize writing a piece in Swedish it means that we can devote less time to our English-language works, which we need to focus on to stay alive in a competitive academic world. But especially in contexts where my research is linked to burning present-day issues whose relevance go far beyond the academic realm, I find myself yearning to write in Swedish, my native language. I also see it as an essential task to act as a mediator between what’s happening in the international academic realm and what’s being discussed locally in Swedish society. Moreover, and needless to say, on a deeper level, writing in Swedish is a fundamental way for us to contribute to keeping our national culture and identity alive.

This autumn I was happy and proud to see my new book in Swedish being published: “Gräv upp, hugg ned, pumpa ut: Människan och naturresurserna under 5000 år“, a kind of popular world history of natural resource extraction and use. The book consists of a longer introductory essay and 13 short chapters, each of which discusses a particular natural resource in global historical perspective: water, wood, salt, gold, iron, coal, sand, ice, aluminium, oil, natural gas, uranium and rare earth elements. It was great fun to write and I was motivated primarily by a strong conviction that this is something that everyone should really know about. The book is intended for a broader, general readership and partly builds on shorter texts that I have written over the years for Swedish-language newspapers and magazines such as Svenska Dagbladet and Forskning & Framsteg. The book also exemplifies how I try to promote the interaction between international academic discourses and local, Swedish societal debates. It is based partly on my own primary research in the fields of energy history and extractivism, but to a great extent also on numerous remarakable works that scholars around the world have produced, from Daniel Yergin’s classical oil history epos “The Prize” to Joachim Radkau’s “Holz: Wie ein Naturstoff Geschichte schreibt”. The latter title may further serve as a reminder of the challange of taking into account, to the extent our language skills permit, key academic works published in languages other than English.

Taking inspiration from Radkau and others, my next Swedish-language book project is a caleidoscopic history of wood, with a particular emphasis on Sweden’s multifaceted experiences with this raw material. Stay tuned for its publication in autumn 2026!

Sometimes you have to do something different from what you usually do. And if you are an historian of technology, sometimes you need to write about things other than technology. So I decided to write a few essays about beaches. I became fascinated by one aspect of beaches in particular: their omnipresence in stories about death. In literature, film and art, as well as in real life, humanity’s relationship with the seashore is dotted by corpses. How can this be? That’s the question that guided me in writing Death on the Beach: Essay from a Marginal World, which has now been published by Barbican Press.

They are countless: the people who for one reason or another – or for no reason at all – have met their fate on the beach. Some have perished in mass tragedies, like when a tsunami hits, destroying everything in its path, or when a foreign fleet arrives and massacres the population of a coastal city. Others have faced their shore doom – as conjured by the forces of darkness or light – alone: sometimes accidentally, sometimes intentionally, sometimes along the harsh path of violence.

The book starts out with an account of famed artist Caravaggio’s tragic death on a Mediterranean beach in 1610. On this basis, I offer a cultural-historical analysis of ancient/classical fears of the seashore. I continue by examining the history of beach murders, indispensable in contemporary crime and horror fiction but with deep roots in medieval fears of the seashore and eighteenth-century worship of the sublime. Then I turn to the early Romantics’ discovery of the seashore and their desire to be swallowed up and ultimately reborn.

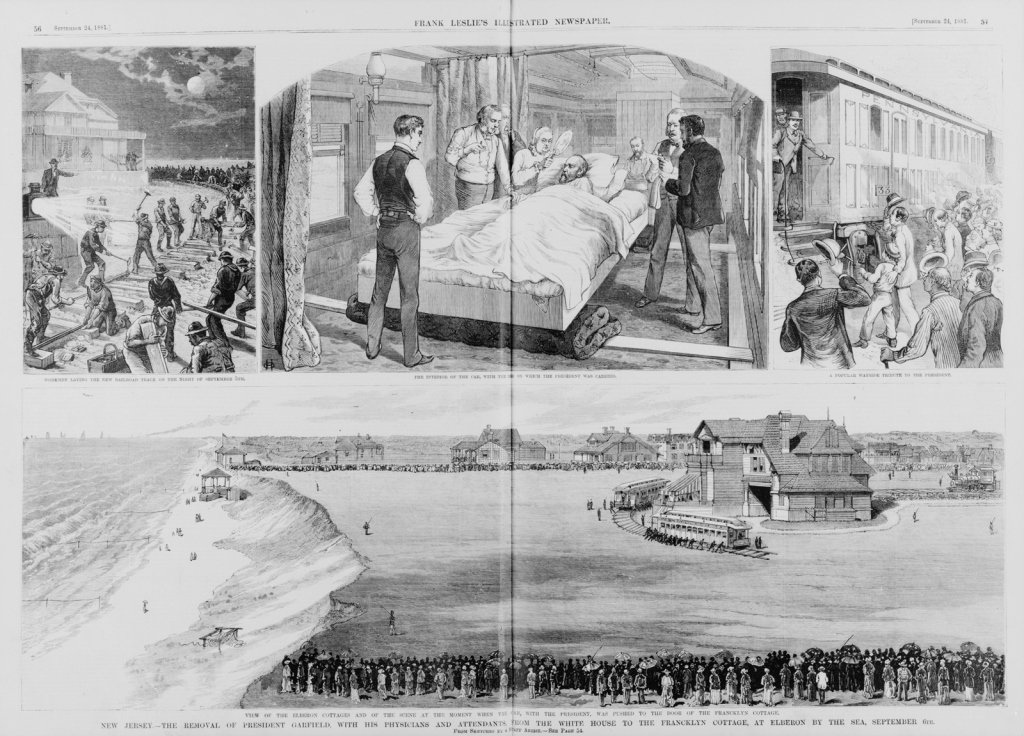

One of my favourite themes, when it comes to the beach as a zone of death, fear and sorrow, has to do with a number of elderly gentlemen’s longing for death in the borderland between land and sea, from fictional characters such as Thomas Mann’s Gustav von Aschenbach (Death in Venice) and Joyce Carol Oates’ Marcus Kidder (A Fair Maiden) to the very real James A. Garfield, the 20th President of the United States.

More often, death on the beach is accidental. For example, many people – and animals – have plunged from cliffs near the sea. This theme is found in, for example, the Gospel of Mark, William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies and the Dover scene in Shakespeare’s King Lear. The tidal zone is also a lethal place, as demonstrated by a film such as Gustavo Montiel Pagés’s Marea de arena and the works of authors like George Crabbe, Walter Scott and Victor Hugo.

In another essay I reflect on the seashore’s amnesic effect: tides and winds quickly erase the world of yesterday and its worries. The paradox is that the beach is also a zone that with greater force than any other landscape evokes memories, especially memories of our dead – a recurring theme in Western fiction, from H.C. Andersen and Marcel Proust to modern science fiction films.

The last five essays in the book spotlight contemporary beach horrors, although history is never far away. Here we encounter the beach deaths of boat refugees in the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea, the rise of beach terrorism in the 2010s, the world’s many historical war beaches, from Troy to Normandy, and the attraction of apocalyptic writers to the seashore, as evidenced by numerous works from Neville Shute’s Cold War classic On the Beach and P.C. Jersild’s After the Flood to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Andrei Tarkovsky’s last film, The Sacrifice.

Death on the Beach was originally published in Swedish in 2020 by ellerströms. I’m very happy that Agnes Broomé agreed to translate the book into English. For the English version, I added a short prologue and a final essay in which I reflect on the beach in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

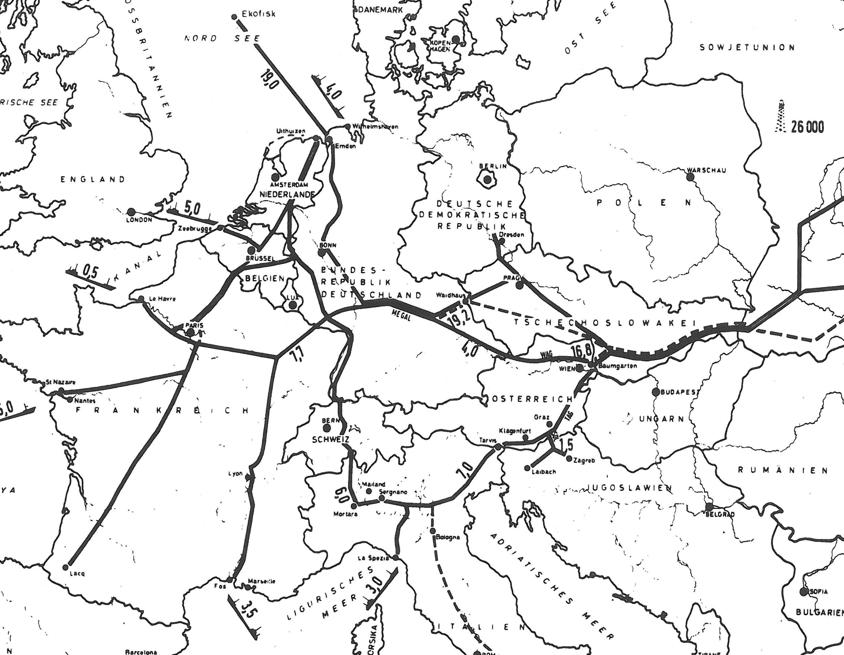

During the Cold War all Soviet gas exports to continental Western Europe took the route through a narrow corridor in Ukraine and Czechoslovakia. Of the capitalist countries, only Finland received Soviet gas through a separate pipeline.

However, both Europe and Moscow early on eyed the need for diversification of the routes. There were plans to build a pipeline through Poland and East Germany, which made perfect geographical sense. But politically, Poland was regarded as unreliable after the 1981 events there.

In the 1970s and 1980s Swedish gas visionaries negotiated with Moscow about extending the Finnish pipeline to eastern Sweden. But Sweden’s low electricity prices made gas unattractive. Today, Stockholm remains the only EU capital that is not connected to the European gas grid.

After the collapse of communism emerging Russia-Ukraine conflicts led to renewed interest in alternative supply routes. From October 1992 Gazprom disrupted flows to Ukraine. Ukraine, facing a debt crisis, was accused of stealing gas reserved for West European customers.

Major new pipeline capacities were taken into operation through Belarus and Poland, with EU support, in the late 1990s. But Russia viewed Belarus as a troublesome partner. In February 2004 Gazprom cut deliveries to Belarus, which had proven unable to pay for its gas.

Then came Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in winter 2004-2005. Gazprom and the Kremlin, along with the Germans, concluded that the time had now finally come to build the Baltic Sea pipeline, which would once and for all serve to make the gas trade independent of Belarus and Ukraine.

A Baltic Sea pipeline was of interest to Britain, too, which from the early 1990s became interested in Russian gas imports. Eastern Sweden, though, continued to be less fascinated by the prospects of Russian gas. Hence the Baltic Sea pipeline would have to circumvent Sweden.

In the 1990s and early 2000s there were different possible route under discussions, notably

1. From Kaliningrad to Denmark and Britain (found feasible in a 1992 study)

2. From Finland to Germany (found feasible in a 1997 study)

3. Directly from the St. Petersburg area to Germany

Gazprom and Finland’s Neste set up a joint venture called North Transgas to explore option #2. But eventually option #3 won out, because why bother to include Finland when you could do without such a small, insignificant, but potentially problematic transit country?

Greifswald/Lubmin in northeastern Germany was eyed as a perfect landing point. A huge old nuclear power complex was being shut down there following Germany’s reunification, and investors hoped to use the infrastructure at the site by replacing nuclear with gas power plants.

Britain hoped to become part of that system, through an extension of the pipelines through Germany and the Netherlands and onwards across the North Sea. In 2003 the UK and Russia signed a “bilateral energy pact”, part of which was devoted to this plan.

In September 2005 Gazprom (51%), Ruhrgas (24.5%) and BASF/Wintershall (24.5%) set up the North European Gas Pipeline Co. (NEGP). It was renamed Nord Stream AG in 2007. Subsequently further shareholders joined cheerfully joined the effort.

Preparations for actually laying the pipeline turned out to be immensely interesting for marine researchers and even marine archeologists. They happily accepted generous funding from Nord Stream for surveying the seafloor.

This generated new scientific insights, and the archeologists discovered numerous old wrecks from different centuries of Baltic Sea history, from Hanseatic vessels to ships that had been sunk during World War II.

In summer 2011 laying of the first Nord Stream 1 pipe was completed. Italian pipe-laying vessels did the job. The second of the two Nord Stream 1 pipes followed a year later.

The Central Europeans didn’t like the project. Poland’s foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski acidly dubbed the project “the Molotov-Ribbentrip Pipeline”. The Scandinavians pointed to the environmental risks.

The other European leaders gathered in Lubmin on 8 November 2011 to ceremoniously and very happily inaugurate the system.

After Nord Stream 1’s inauguration the debate about it lost momentum for some time. The pipeline apparently operated smoothly.

The debate resurfaced in June 2015, when Gazprom and five European energy companies announced their agreement to build Nord Stream 2. The deal was very controversial due to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and support to separatist military forces in Donetsk and Luhansk.

A bad omen for the future came in early November 2015, when an unmanned underwater vehicle was found on the Baltic Sea floor, off the Swedish island of Öland, just next to one of the two Nord Stream I pipes. It was loaded with explosives.

The Swedish Armed Forces later confirmed that it was a Swedish military vehicle. It had gone astray during a military exercise held elsewhere in the Baltic Sea several months earlier. This was in the midst of the European refugee crisis and the event didn’t make many headlines.

There was a fierce debate about whether Nord Stream 2 was actually needed. Critics noted EU gas demand, after half a century of rapid growth, had reached a plateau level and even seemed to be set for decline. No future growth in demand was expected. So why build a new pipeline?

Proponents of Nord Stream countered by pointing out that natural gas had a key role to play in the European energy transition: Russian or not, natural gas was a flexible source of electricity that could compensate for irregularities in wind and solar electricity production.

Proponents of Nord Stream 2 also pointed to another critical trend: internal West European gas production was declining helplessly, especially in the Netherlands. Internal EU production collapsed during the 2010s, falling by nearly two-thirds (!). Who would cover the deficit?

The EU Commission’s answer was: “Let the market decide!” Since Russia offered the cheapest gas, its exports increased massively in the increasingly liberalized EU gas market. Russia’s share of EU imports climbed from 31% in 2010 to 40% in 2016 and then stayed on that level.

Over time, this growing Russian dominance made EU agencies and national governments increasingly suspicious (while gas companies remained happy). The EU commission changed its mind about Nord Stream 2.

There were also critics on the other side of the Atlantic. Already the Obama administration lobbied against Nord Stream 2. This served two purposes: preventing Russian geopolitical influence in NATO member states and boosting US shale gas exports to Europe.

In the meantime preparations for laying Nord Stream 2 started. Several Swedish coastal municipalities wished to become involved in the project logistics. The Swedish Foreign Ministry sought to prevent them, but in vain.

Starting in October 2017, 52,000 Nord Stream 2 pipes were brought to the port of Karlshamn in southern Sweden, for temporary storage. This meant a welcome additional source of income for the Swedes. In 2018 the pipes started to be lowered into the Baltic Sea.

Then, Donald Trump stepped up the drama by imposing sanctions on companies that were involved in planning and constructing Nord Stream 2.

in December 2019 Allseas, a pipelaying company contracted by Nord Stream 2, gave in to US pressure. It abandoned the project, pulled out its vessel and moved it to Kristiansand in southern Norway.

This could not stop the project. It merely delayed it. Nord Stream 2 contracted a Russian pipelaying vessel and completed construction in September 2021. An intense struggle followed: should the pipeline be allowed to become operational or not?

Completion of Nord Stream 2 coincided with federal elections in Germany, which brought to power not only the Social Democrats, but also the Liberals and the Greens, which were much more critical to Russian gas than Angela Merkel’s resigning government.

The decisive blow to the project came with Germany’s decision to suspend certification of the pipeline on 22 February 2022, as a punishment on Russia for recognizing Donetsk and Luhansk as independent republics.

Two days later, Russia launched a full-scale military assault on the rest of Ukraine, including Kiev. Nord Stream 2 filed for bankruptcy already on 1 March 2022.

In June the gas flows along Nord Stream 1 were reduced by 60% “due to renovation work” and in July it was totally shut down for maintenance. EU governments started to prepare for a winter without Russian gas.

A turbine from one of the compressor stations was sent to Canada for technical overhaul, enabled by an exception from the sanctions. After 10 days this turbine was back in operation and the gas flow resumed, though only at the previous 40% level.

A week later the flow was reduced again to a mere 20% due to “technical problems” with one of the turbines. Shortly afterwards, on 31 August, the pipeline was fully closed due to “repair works” and more “technical problems” (Gazprom cited an oil leak in one of the turbines).

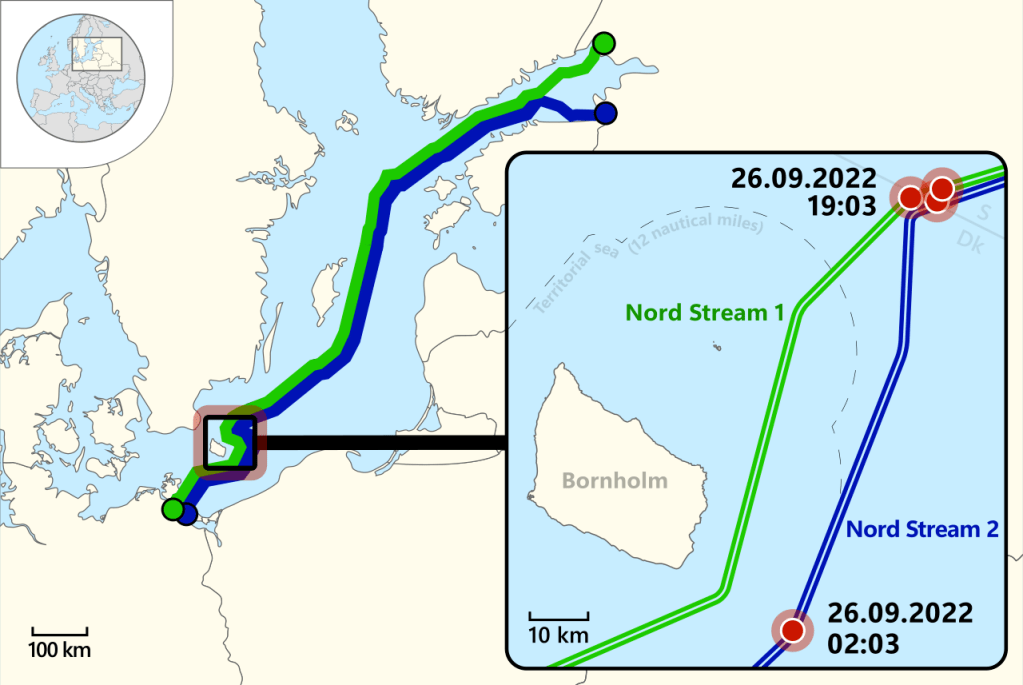

Then, on 26 September, several leaks in all four subsea pipelines were found in the Danish and Swedish economic zones. It quickly became clear that it was a result of violent sabotage. It remains to be seen whether Nord Stream 1 and 2 will ever go into operation again.

Map of Nord Stream 1 and 2, and the September leak (Wikipedia)

There was a time when virtually all my academic activities gravitated around the Baltic Sea. For a number of years, I travelled along its coasts, attempted to learn its languages and read everything I could find about its history. I spent a year and a half in Greifswald in Pomerania, where I wrote my master’s thesis, then a year in Tallinn and Tartu in Estonia, where I did research for my PhD thesis. And of course I spent numerous summers in Kvarnåkershamn on Gotland, where we have a summer house. In 2007 I wrapped up my experiences of the Baltic Sea world in a travelogue, “Östersjövägar”, which let the past confront the present and the personal meet the professional.

Since then my geographical focus has been less distinct, as I have become engaged with wider European and global issues. The NUCLEARWATERS project, however, which aims to rewrite the global history of nuclear energy through the lens of water, has allowed me to partly return to the Baltic Sea: one of the six case studies addresses the “Nuclear Baltic”. Earlier this month I had the chance to present tentative results of it at this year’s Baltic Connections conference in Jyväskylä, Finland. I had been invited to give one of the keynote lectures, and decided to make use of the opportunity to discuss the ongoing nuclear-historical research that my colleagues at KTH and I are currently doing with a multi-disciplinary crowd of scholars from Finland, Scandinavia, the Baltics and beyond.

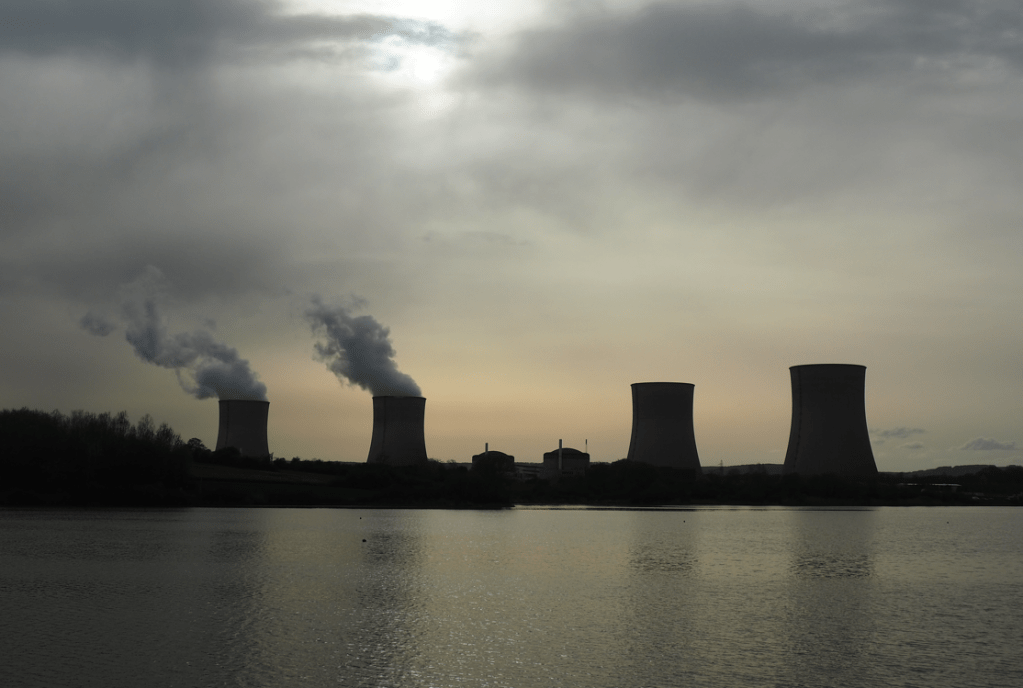

The notion of the “Nuclear Baltic” reflects a desire to move away from the nationally oriented nuclear histories that so far has dominated the literature and, instead, take the Baltic Sea region in its entirety as the point of departure for analysing nuclear’s past and present. There is good reason to do so, especially if we view the history of nuclear energy through the lens of water. Finland, Sweden, the Soviet Union and East Germany all built nuclear power plants on one or the other Baltic coast, making use of the same brackish water for the plants’ cooling needs. Denmark also planned to erect a Baltic nuclear plant, but eventually opted not to go nuclear at all. Poland started to built a large NPP near the Baltic coast, although in this case the nuclear builders, for reasons still not entirely clear to me, preferred to use a lake rather than the Baltic itself for cooling. Nuclear engineers tamed the Baltic Sea, adapting the coastscape to their specific needs, while the sea itself occasionally also “revolted”, causing problems for the nuclear plants. Nuclear builders, moreover, interacted intensely with fishing, navigational and recreation activities. The plants were usually built in places that were popular spots for bathing, swimming, hiking and sailing.

After 1989, the nuclear power plants that had been erected on different Baltic shores started to interact with each other in very interesting ways. The collapse of communism on the Baltic’s eastern shores made it much easier for actors on the Baltic’s western shores to access information about nuclear developments in the east. This partly generated new fears in the West about the dangers of Soviet-designed NPPs. Finland, for example, was increasingly worried about the Chernobyl-type reactors at Sosnovy Bor. Denmark, for its part, had traditionally been extremely critical of the Swedish Barsebäck NPP, but towards the late 1980s this was more and more accompanied by fears of the Greifswald NPP as well. Sweden, too, worried both about Greifswald but even more about Ignalina and its Chernobyl-type reactors.

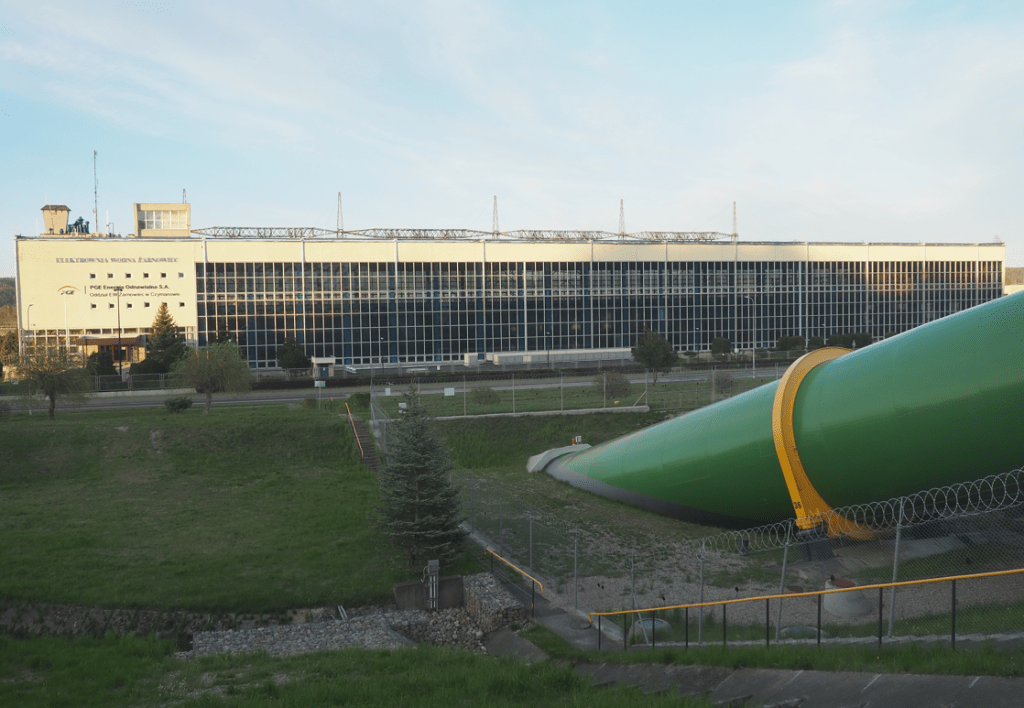

But there were also new hopes. The collapse of communism and the end of the Cold War opened up for new forms of hands-on technical cooperation between East and West. Nordic and West German nuclear engineers became very engaged in improving the safety of Soviet-designed plants. Moreover, the closure of the closure of the ex-GDR’s Greifswald NPP (which I have written a book about long ago) enabled engineers to take a close look at the decommissioned reactor vessels and examine safety problems related to things like pressure vessel embrittlement in Soviet-type reactors. These studies proved very useful especially for the Loviisa NPP in Finland, which had two very similar pressure vessels. The Loviisa reactors had for some time experienced embrittlement problems, and the study of the decommissioned Greifswald pressure vessels led engineers to devise effective engineering solutions to that problem. There was a similar interaction between Finland and Poland. The Poles had abandoned their work on the Zarnowiec NPP after the Chernobyl disaster. The Finns then asked the Poles if they could purchase one of the Polish reactor vessels, along with various other equipment, with the idea of using them for training purposes in Finland. These are fascinating examples of transnational dynamics in the post-Cold War nuclear Baltic.

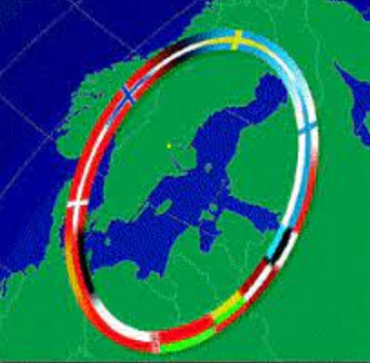

At another level, the end of the Cold War ushered in a new era of transnational cooperation in the field of electricity system-building. A mix of political and technological visionaries suggested that an integrated electricity grid and a common electricity market in the Baltic Sea region could serve as a powerful example of Baltic Sea cooperation more generally and, following a Kantian and Saint-Simonian philosophical tradition, contribute to political stability, international understanding and peace. This became the starting point a project that was popularly referred to as the “Baltic Ring”. Actors envisioned new subsea electrical connections between Finland and Estonia, between Lithuania and Poland, between Lithuania and Sweden, between Poland and Sweden, and so on – connections that would serve to unite the Baltic Sea both materially and symbolically.

There was at least one problem with these new proposed interconnection projects: there were radically different interpretations about the actual purpose of the subsea cables. To understand this we should first observe that, for example, the Ignalina NPP in Lithuania had traditionally served electricity needs not only of Lithuania itself, but also of neighbouring regions in the ex-Soviet realm, especially Russia and Belarus. In the 1990s, then, Lithuania’s nuclear exports to these countries was expected to be phased out. In this situation, the Lithuanians hoped to compensate for its loss of export revenues by shifting its nuclear electricity exports to the Nordic region and Poland. Hence from a Lithuanian perspective the purpose of the “Baltic Ring” was to enable a restructuring of Lithuanian nuclear electricity exports. This vision contrasted starkly with Nordic and in particular Swedish visions. The Swedes regarded a potential new electricity connection between Lithuania and Sweden as a way for Sweden to strengthen the Lithuanian electricity system and, by extension, make it possible for the Lithuanians to close down their dangerous nuclear power plant. These very different interpretations was a key reason for the very long delay of the proposed link between Sweden and the Baltics; it was finally implemented only in 2015 – nearly a quarter of century after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the case of Poland, the decision to abandon the Zarnowiec NPP was detrimental to Polish electric grid stability. It was clear to electricity system builders that a new source of electric power was direly needed in the northern part of the country. The post-nuclear solution, however, was not to build a coal power plant or a gas power plant in northern Poland. Instead, Poland and Sweden agreed on laying down a subsea electricity cable under the Baltic Sea, through which Poland was given access to Swedish nuclear electricity. The cable, which was eventually inaugurated in 2000, landed in the port of Ustka on the Pomeranian coast, not far from the ruins of Zarnowiec. So all in all, when we read about the electricity cables that now criss-cross the bottom of the Baltic Sea, we should view them as components in a wider transnational struggle for and against nuclear energy in the Baltic Sea region.

A final chapter in the Baltic’s nuclear history has to do with how the Baltic Sea itself has gradually emerged as a threat to nuclear safety. The environmental situation in the Baltic Sea has been deteriorating for decades, in ways that the nuclear builders of the 1960s and 1970s could hardly have imagined. Since the 1980s, in particular, the Baltic Sea has seen enormous problems with eutrophication and algal blooms, much highlighted in the general media. In addition, the Soviet Union and then Russia has increased its oil exports enormously, and much of this oil is shipped through the Baltic on its way to foreign markets. These developments now pose a major threat to nuclear safety, or so nuclear engineers and power plant operators think. More precisely, what they fear is that the supply of cooling water might be compromised or disrupted for one or the other reason.

The most severely affected nuclear pant in this respect – so far! – appears to be the Finnish Loviisa facility, situated as it is in a vulnerable spot on the Gulf of Finland, where Russian oil tankers pass by and which is also susceptible to algal blooms. In response to this, the nuclear operator, Fortum, in 2013 announced a new investment program, centering on the construction of special cooling towers to “improve safety in extreme conditions when seawater becomes unavailable for cooling, such as an oil catastrophe in the Gulf of Finland, or an exceptional natural phenomenon such as excessive algae growth.” In this way the Baltic Sea, which historically seemed to offer a perfect source of cooling water, in a way that was seen to guarantee nuclear safety, is nowadays turning into a threat to nuclear safety, and nuclear engineers are now very busy devising technical solutions to cope with these perceived dangers. It remains to be seen how the marine environmental situation in the Baltic Sea continues to interact with nuclear developments. In any case, the history of the Nuclear Baltic is still very much a history in the making.

One of the most rewarding parts of my academic life during the past months has been my field work on nuclear energy and, in particular, nuclear’s multifaceted connections with hydraulic engineering – a key theme in my ERC-funded NUCLEARWATERS project at KTH. This work has taken me to nuclear sites in Germany, Sweden, France, Luxembourg and most recently also to Poland. I started out in September last year, staying on a few days in Bavaria after my participation in a Regensburg conference (see my separate blogpost about that meeting, where I gave a keynote talk on “Transnational Infrastructures in an Age of Border-Building). By car, train, and bicycle I explored the water flows, hydraulic history and nuclearized landscapes around the Gundremmingen nuclear power plant (on the upper Danube), the Isar plant (on the Danubian tributary with the same name), and the Grafenrheinfeld facility (which is on the Main and hence in the Rhine river basin).

This was so inspiring and useful that I decided to combine later conference and archival trips with visits to further nuclear sites. In November this brought me to three nuclear power sites on the Lower Elbe, just downstream from Hamburg, where German utilities from the 1960s to the 1980s erected the Stade, Brunsbüttel and (the highly controversial) Brokdorf nuclear stations.

This spring I continued the work by travelling up the Moselle, a Rhine tributary whose cooling potential has historically captured the imaginations of nuclear visionaries in Germany, Luxembourg and France alike – although in the end only France actually built a plant: the huge Cattenom NPP, around 15 km upstream from Schengen at the French-German-Luxembourg border.

Most recently, our NUCLEARWATERS team travelled together in the historical footsteps of Swedish nuclear engineering. We drove south from Stockholm along the Baltic coast to Studsvik, an iconic site in Swedish nuclear history that came to host several research reactors, then onwards to Marviken, an ambitious but ultimately failed project whose physical remains are still worthy exploring for anyone interested in the “Swedish line” of nuclear engineering: the country’s historical ambition to combine civilian, heavy-water-moderated nuclear reactors with the development of nuclear weapons. We then paid a visit to the Äspö Laboratory, next to the Oskarshamn NPP in southern Sweden, where research is being carried out 500 meters underground since several decades, as part of the Swedish nuclear industry’s efforts to build a final repository for spent nuclear fuel.

From Oskarshamn I continued – without my colleagues, unfortunately! – to Karlskrona and onwards by ferry to Poland. There, I explored Lake Żarnowiec, where communist Poland started to build a large nuclear power plant in the late 1970s. The idea was to combine it with a pumped-hydropower plant. While the nuclear plant was abandoned following the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, the hydropower plant was completed, including construction of an impressive artificial lake in the hills above Lake Żarnowiec. I then continued westwards along the Baltic coast, familiarizing myself with the radical “anti-atomic chapel” in Gąski, a Catholic site of worship created in 2012 as part of popular protest in the area against the government’s plans to revive nuclear construction; the (ultimately failed) plan envisaged a full-scale nuclear power plant there.

What, then, can historians gain from visiting sites like these? What do “nuclear journeys” like these add to what we already know about nuclear history, or to what we may find in the archives? My answer is: a whole lot. Firstly, actually visiting the sites is necessary to gain a sense of the physical size, the geographical scale, the architectural forms and the materials drawn upon in nuclear projects. Secondly, site visits makes you see things at a nuclear site and in a nuclearized landscape that have typically been of central importance, although they have been toned down in – or simply omitted from – the documentary sources and official narratives. This concerns, in particular, hydraulic components like dikes, canals, pumping stations and cooling water discharge facilities. Thirdly, by exploring a site you become aware of how the nuclear facility is integrated into a wider – half natural, half built environment (Żarnowiec is a case in point). Fourthly, site visits opens up for an in-depth understanding of how nuclear facilities tie into local histories and cultures. Hence many nuclear sites coincide with environments that in the past have featured in key political and military developments, or have attracted writers and artists, or were subject to non-nuclear resource extraction. All this is extremely helpful for any historian who wish to write “relational” nuclear histories – which is what I’m convinced we need to do.

My first trip abroad after the onset of the pandemic took me to the lovely Bavarian city of Regensburg, whose Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies (IOS), Germany’s main hubs in this loosely defined field, had invited me to give a keynote lecture at their annual conference. The conference theme was very timely: “Infrastructure in East and Southeast Europe in Comparative Perspective: Past, Present and Future“, and I couldn’t resist the temptation to use the occasion to place present-day infrastructural and societal challenges in Europe in historical perspective, by discussing them in relation to 200 years of contentious European system-building activities.

But not only system-building; my overarching argument was that any analysis of transnational system-building also has to take into account the dynamics of “border-building”, a concept that I have earlier explored together with Arne Kaijser and Erik van der Vleuten in our contribution to the Making Europe book series, “Europe’s Infrastructure Transition: Economy, War, Nature“. I argued that it is precisely in the interaction between system-building and border-building that we must look for the essence of what transnational infrastructures are really about and how they function (and don’t function!) in a rapidly changing world. In Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the co-evolution of system- and border-building is currently demonstrated by the intriguing combination of transnational system-building visions such as the ones promoted by the state-led Three Seas Initiative, and parallel efforts to strengthen border controls and make it more difficult for people and goods to make it across national borders in the region.

I suggested to examine the dynamics of system- and border-building by conceptually distinguishing between two different logics that in a longue durée perspective can be seen to have shaped the dialectics of systems and borders over longer periods of time. I referred, on the one hand, to a “techno-economic” logic, and on the other, a “geo-political” logic.

The techno-economic logic allows us to see how technical and economic development historically generated a demand for a more open world featuring an ever denser network of cross-border interconnections and flows. This development repeatedly generated a counter-trend in terms of demands for stricter border controls and reduced flows. The resulting dialectics can be traced back to nineteenth-century demands to remove “artificial” infrastructural obstacles such as the tolls collected along rivers, and it ends, for the time being, with the efforts of border-builders in our own era to close Europe’s borders to immigrants.

The geo-political logic, by contrast, is about the interplay between shifting political geographies and national and transnational system-building activities. The starting point here is the observation that infrastructures have always been developed with a certain political geography in mind. When this political geography changes, the existing systems no longer seem to match or fit the new geopolitical realities. This has historically generated a desire from the side of both system-builders and border-builders to do something about this. This logic was perhaps most pronounced following the end of World War I, but it is nowadays equally omnipresent all over Central and Eastern Europe. There, following the collapse of communism in 1989, many countries are still in the process of trying to adapt communist-era systems to the new political geography of Europe. This has in many cases been an exceedingly slow process, as testified by the still unsuccessful attempts by, for example, the Baltic countries to break away from the Soviet-era electricity grid, through which they remain tied to both Russia and Belarus.

On 19 April I was invited to give a talk on “usable pasts” as the first in a series of events on this theme in the Berlin-Brandenburg colloquium for environmental history. It stimulated me to think through, based on my personal experience, some intriguing issues concerning the relationship between historical research, present-day societal challenges, and interaction with other, non-historical scholarly fields.

The talk is available online here.

I argued that historians are not well equipped to come up with concrete policy advice or propose solutions to various present-day problems. This means that I am not very enthusiastic about taking an “activist” stance. Of course, I do respect my colleagues who do that, but in most cases such activism is not really based on the historical expertise of the historians-activists, but more on the opinions and ideas of historians in their capacity as highly educated and concerned citizens. More importantly, it seems to me that historians are well equipped to engage and participate in the public debate in more indirect ways. I argued that they can do so in two main ways, which are important to separate from each other: empirically and theoretically:

Empirically, historians can enrich the debate by “zooming out”, temporally and spatially. Actors and analysts of current affairs are often surprisingly unaware of the wider historical context in which many burning issues of the present are part. Worse, they often mobilize distorted and “fake” histories to advance their arguments. Clearly, historians have a moral duty to oppose this by unpacking the historical complexity of the present. Based on examples from the fields of energy and water history, I argued that it can be extremely fruitful to do so not merely by writing opinion pieces or giving radio and TV interviews, but rather by making the link between past and present explicit in academic books and articles.

Theoretically, historians can mobilize concepts and theoretical ideas generated in the context of historical research, and apply them to present-day burning issues. This creates a basis for systematically engaging in debates about analogies between current issues and historical events. In this case there is no need for an empirical overlap, in the sense that conceptualizations of, say, medieval forestry can be of relevance for engaging in twenty-first century debates about electrical vehicles. Theory-based analogies can and should be mobilized not only for developing new “perspectives” on current affairs, but also for warning present-day actors about what can go wrong. Unfortunately, many false and “fake” analogies are always circulating, and over-simplifications are common. Paradoxically, however, I argued that at the theoretical level, historians actually need to simplify in order to make sense of their contributions to the debate.

The event was also part of the Environmental History Week organized by the American Society for Environmental History (ASEH).

I have written earlier on this site about a Tensions of Europe (ToE) workshop that I organized in Stockholm back in June 2018 under the heading “Challenging Europe: Technology, Environment and the Quest for Resource Security” (see this blogpost). The event was part of one of the theme groups that we have set up under the ToE network umbrella, targeting the history of natural resources in Europe and beyond. At the Stockholm workshop, for which we were lucky to receive generous funding from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, we discussed 15 draft papers and eventually came up with an ambitious plan for publishing the papers jointly in the form of three special issues, for three different journals.

Two years later, I am now amazed to see how well the plan worked out in the end: all workshop participants, who are at home in 8 different countries, did manage to finalize their articles, and all the three special issue proposals actually materialized. This is simply fantastic! The experience testifies, in a most powerful way, to the great intellectual value of the “writing workshop” format that we tried out: there were no paper presentations, but the entire workshop was geared towards reading, commenting, discussing, and rewriting of draft papers – partly in smaller groups, partly in plenary sessions.

Christian Kehrt and John Martin took the initiative of organizing one of the special issues, which in the end was entitled “Reconfiguring Nature: Resource Security and the Limits of Expert Knowledge” and was published in Global Environment. The special issue includes an introductory piece and five in-depth articles authored by Anastasia Fedotova, Elena Korchmina, Nkemjika Chimee, Jiří Janáč, John Martin, and Christian Kehrt. The objects of study range from forests and rivers in Central and Eastern Europe to extractive infrastructures in colonial Nigeria and the quest for Antarctic krill. A must-read collection!

Meanwhile Anna Åberg and Frank Veraart organized a second special issue, which in this case was published in The Extractive Industries and Society. It had the title “Creating, Capturing and Circulating Commodities: The Technology and Politics of Material Resource Flows, from the 19th Century to the Present.” Again, the introductory piece is here followed by five in-depth studies, conducted by Alexandra Bekasova, Hanna Vikström, Anna Åberg, Maja Fjaestad, Karl Bruno, Frank Veraart, Jan-Pieter Smits, and Erik van der Vleuten. Here we may read about limestone extraction in Imperial Russia, critical metals in renewable energy technologies, transnational flows of uranium, iron-ore mining in Cold War Liberia, and the connected sustainability histories of the Rhine and the Niger deltas – all of it greatly fascinating.

Last but not least, Ole Sparenberg and Matthias Heymann championed a third special issue, entitled “Resource Challenges and Constructions of Scarcity in the 19th and 20th Centuries.” It was published in the European Review of History/Revue européenne d’histoire and, just like the other two special issues, it included an introductory article and five in-depth pieces, written by Marina Loskutova, Sebastian Haumann, Matthias Heymann, Julia Lajus, and Ole Sparenberg. Topics range from fears of deforestation in the Volga region and resource scarcity predictions in the Soviet Union to the remarkable career of limestone in Germany and global metals crisis of the 1970s. Highly recommended reading!

It’s safe to say that this impressive output from a single workshop could not have happened over Zoom. I will be eagerly looking forward to a time, hopefully not in a too distant future, when “writing workshops” of this kind can once again be safely held.

Intellectually speaking, I seem to be moving between two extreme geographies: on the one hand, I thirst for reading and writing about the seaside, the beaches and the coastscapes of the world; on the other, I bury myself into studies of the strange, dry interiors of Eurasia. This spring I was supposed to have spent two weeks in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, linked to my contribution to a special issue in the Central Asian Survey and a workshop that was scheduled for facilitating it, to be held in Bishkek, organized by my brilliant German fellow historians Jonas van der Straeten and Julia Obertreis. Unsurprisingly, the workshop couldn’t take place physically, but the organizers heroically turned the event into a digital one. It became my first-ever online conference. The theme? “Technology, Temporality and the Study of Central Asia”.

Central Asia’s modern history is very much a history of Russian colonialism. In this sense the online workshop came up at precisely the right moment, because I’m currently also working together with four Swedish colleagues on finalizing a co-authored book with a colonial-historical angle. Based on two large research projects that we recently concluded, the book targets Sweden’s role in the African, Asian and Arctic exploitative colonialism. My own focus here has been on Asia, and especially Russia and the Soviet Union, starting with the Swedish Nobel Brothers’ pioneering role in Russian petro-colonialism – centred in the Caucasus but later expanding into Central Asia, Siberia and the Far East – and ending with state-led Swedish efforts to tap into the Soviet Union’s colonial resource wealth.

Both the Bishkek workshop and the Swedish project have given me an excuse to devote quite some time recently to reading about the history of Russian colonialism more generally. The most fascinating book that I’ve come across here is Alexander Etkind’s Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience (2011), which retells Russian political and cultural history as “a history of country that colonizes itself”.

I have to admit I always thought the notion of “internal colonialism” was a post-World War II academic term, but in Etkind’s account it becomes clear that it was a guiding concept for exploring the very essence of the Russian Empire early on, and practically all pre-1917 (Russian and foreign) intellectuals made use of the term. Etkind nicely problematizes the intricate interaction between Russian settler colonialism in areas primarily populated by non-Russian peoples – Siberia, the Volga basin, the Caucasus, Central Asia, etc. – and what the colonial-style histories of the Russian heartlands. I’m deeply impressed by the way Etkind turns Russian history into transnational history. Moreover, he manages to bridge political power issues (in a discussion inspired by Hannah Arendt) and exploitative economies and ecologies (from fur pelts to fossil fuels) with a cultural history featuring well-known writers like Gogol but also strange, unreliable thinkers like Vasilii Tatishchev (who believed that the Russian people stemmed from a mix of Scandinavian Vikings and African Amazons).

However, as one of the participants in our Central Asia workshop, Oybek Makhmudov, made clear to me, the very idea that Russia has a colonial past remains controversial in the scholarly community – especially so in Russia itself. Needless to say, this makes the theme even more fascinating, and so I will continue reading and writing.

As you may have noticed, I’m probably one of the laziest bloggers in the world: in a good year I produce perhaps 4-5 blogposts, sometimes a bit less, sometimes a bit more. Now, seeing that I wrote my last post on this site three months ago, I get the feeling that I need to prove I’m still alive. So here is a brief summary of some of the things I’ve been up to this autumn (and I can tell you it’s still autumn in Stockholm, no winter yet in sight!).

In terms of research, I have had two main foci: on the one hand I have been working on finishing up our exciting project on Swedish resource colonialism, mentioned on this site a couple of times in the past few years. Together with my colleagues Dag Avango (who is now professor of history at Luleå University of Technology), Hanna Vikström (currently a post-doc at Umeå University) David Nilsson and Karl Bruno, I’m wrapping up several years of research in an English-language monograph. It will be completed, as far as the writing is concerned, by June 2020. In relation to this project I also spent some of the autumn working on shorter essays and articles on the history of natural resources from different perspectives, including a review essay piece on the historical dynamics of resource frontiers, through which I really felt I learnt a lot. It will soon be published in the German NTM journal. Another piece focuses on resource extraction in twentieth-century history as part of a larger, multi-author book project on the cultural history of technology, to be published by Bloomsbury in 2022.

On the other hand, our big ERC project on the history of nuclear energy, NUCLEARWATERS, continues to gain momentum and it has been one of my greatest pleasures this autumn to see how my three PhD students – Alicia Gutting, Achim Klüppelberg and Siegfried Evens – who work in the project have all made remarkable progress. They have done impressive archival research in Germany, Belgium, Austria, Sweden, Estonia and Russia, while also developing new surprising ideas of a more theoretical nature. I am being helped in advising the three student-researchers by my brilliant senior colleagues Kati Lindström and Anna Storm. Anna was recently appointed professor of technology and social change at Linköping University, but will stay in our project throughout its life-time. In January I will be welcoming an additional senior researcher in the project, Roman Khandozhko from Russia, who has earlier been working in another big nuclear history project at Tübingen in Germany. If you are interested in my own work in NUCLEARWATERS, you can take a look at this video that was recorded while I presented some of my finds in Helsinki a few weeks ago. NUCLEARWATERS also has its own website and blog, which by now lives its own life.

Since 2018 I am also running a research project called Cold War Coasts. Like NUCLEARWATERS, it has (since a few months) its own website and blog. In January 2020 I will be publishing a first outcome – or rather a kind of bi-product – of this project, in the form of a thin book in Swedish language, called “Döden på stranden“. In the book I sketch how numerous seashores have been places of fear not only during the Cold War era, but throughout human history. I will come back to the book once it has been published early next year. During 2019 we established a promising cooperation with Tallinn University for carrying out the Estonian case study in Cold War Coasts. During 2020 we will start our real work on the case studies.

I have not done much teaching this autumn. But on those occasions when I did teach, it struck me how valuable and necessary it is for a scholar – at least when you can choose relatively freely what to teach. The teaching world in my department is really upside-down: we are not, like many others, struggling with heavy teaching loads, but, on the contrary, eagerly looking out for new teaching opportunities. The reason is that we do not have any programme of our own, but merely run a few courses that are mostly elective or voluntary. Nobody in our department has a teaching load of more than, say, 20%, which might sound like paradise for anyone who dreams of doing more research and less teaching. But the backside of the coin is that what we do, which is mainly research, can only be sustained through continued success in raising external research grants. So far that has worked fairly well, but who knows for how long?

In relation to teaching, another nice part of my academic life this autumn has been a new cooperation with the Liber publishing house in Sweden and two secondary school teachers at Anna Whitlocks gymnasium in Stockholm, Mimmi von Plato and Henrik Wiberg. I am cooperating here with my KTH colleagues Nina Wormbs and Cecilia Åsberg. The idea, which is now materializing, is to place the historical, social, political and cultural perspectives centre-stage in Swedish secondary schools’ technology programme. So from next year, technology students in our country will be basing their learning on quite a different coursebook than what has been available so far!

A final autumn highlight that I must mention was my trip to Italy in October. I went there primarily for the SHOT annual meeting in Milan, but I also took the opportunity to explore the Po Valley’s nuclear geography and history. Then, I took the train down to Rome to interview Felice Vinci, a former nuclear engineer who, following Italy’s nuclear phase-out in the aftermath of Chernobyl, turned to the Greek classics and launched the theory that the Iliad and the Odyssey are, in fact, set in the Baltic Sea. Read my NUCLEARWATERS blogpost on this, and, if you can read Swedish, check out my newspaper essay on Vinci’s Baltic theory, published back in 2008!